This post was co-written with Angus Crichton for the blog of the African Books Collective (https://africanbookscollective.com/)

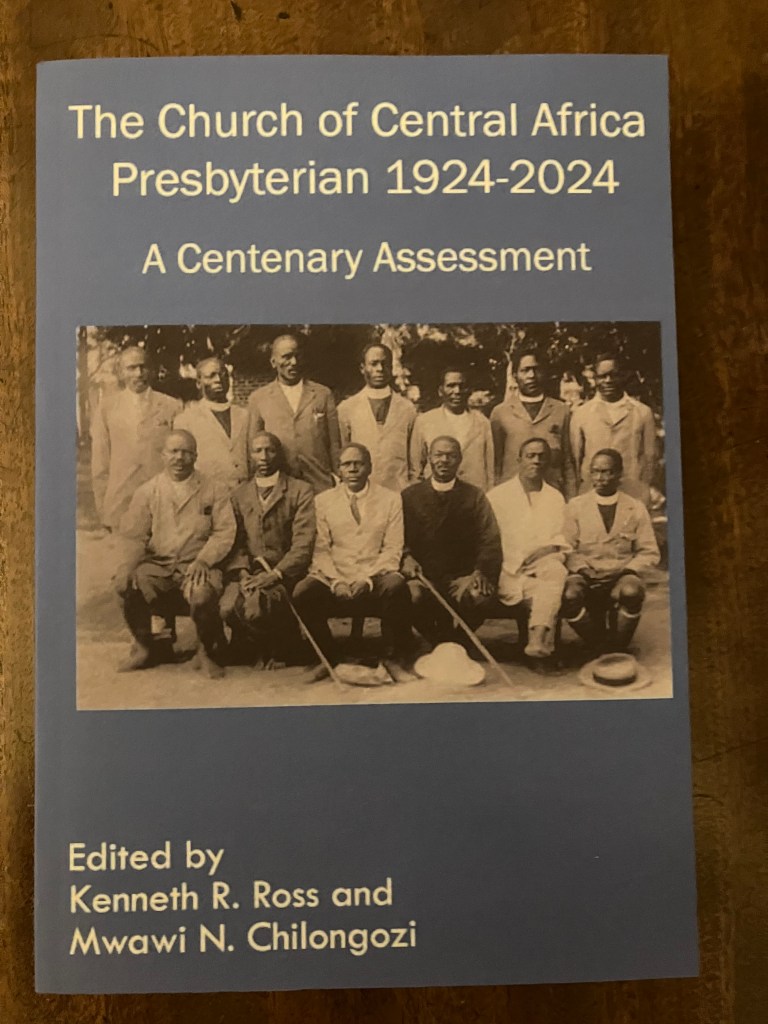

In 2024, the Malawian publisher and African Books Collective (ABC) member Mzuni Press published The Church of Central Africa Presbyterian 1924–2024: A Centenary Assessment. In this blog, its editor, Kenneth Ross and Angus Crichton situate this publication within wider trends on publishing scholarship on African Christianity, based on their experience of theological publishing in Malawi and Uganda, respectively.

Readers of this blog scarcely need reminding about the extraversion of African intellectual property northwards. The African publishers within ABC labour daily to craft African content by Africans, in Africa, for Africa and, via ABC’s distribution systems, to offer this as a benediction northwards. The extraversion of African Christian thought is particularly ironic in the face of global Christian trends. In 1900, approximately 82% of Christians were in the Global North, with 18% in the Global South. A recent projection to 2075 suggests an almost complete reversal – 17% in the Global North and 83% in the Global South. The massive accession to the Christian faith in Africa has been central to this reversal. At the start of the twentieth century, the African continent made up 2% of the world’s Christian population, with its heartlands residing in Europe and North America. At the quarter-way marker of the twenty-first century, around 30% of the world’s Christians are in Africa. The projection to 2075 suggests that almost half of the world’s Christians will be Africans (1.8 billion).

Yet the infrastructure to craft African Christian thought informed by African realities is still over-dependent on the knowledge ecosystems of Euro-America. This is not the case for other new heartlands of the faith, for example in Latin America or South-east Asia. To take one example, in the last ten years some seven multi-author compendia of doorstop proportions have been published on African Christianity. In contrast to their 1950s counterparts, there has been a welcome reduction of pale-faced contributors such as ourselves. However, these volumes are still published in the Global North, with the latest weighing it at over 700 pages and a £250 price tag. For one African contributor, such pricing created a prohibitive customs fee on their complimentary copy in their African country of residence, let alone allowing meaningful distribution on the continent as a whole. Meanwhile, well-intentioned Christian organisations in the North continue to funnel predominantly Euro-American Christian publications into educational institutions and bookshops on the continent. The net result echoes Ali Mazrui’s dictum: Africa consumes what it does not produce and produces what it does not consume.

At this point, we could give way to the familiar trope of lamenting the state of African scholarly publishing and make recommendations for what could or should be done in response. However, in the spirit of ABC’s publishers, a small cadre of African theologians and publishers have moved beyond lamentation to action. Indeed, two Malawian publishers are numbered among ABC’s publishers: Kachere and Mzuni Press. The latter published The Church of Central Africa Presbyterian 1924–2024 in 2024, a multi-authored volume of essays by mostly Malawian authors to mark the centenary of a major Christian denomination in the country.

The book was not only published in Malawi for the benefit of its most significant audience, but also co-published with Barnabas Academic in South Africa (which has historic ties to the Presbyterian Church in Malawi), distributed via ABC into the Global North and made available for free-download by Globethics Publications out of Switzerland. Few academic powerhouse presses either side of the Atlantic have such comparable global reach. Mzuni Press has achieved this with a substantially more limited publishing infrastructure: gratis skeleton editorial and production generalists in contrast to a phalanx of salaried specialists, offset versus Print on Demand (POD) printing, and the trusted book table versus desktop to doorstep purchase pipeline. As for intra-continental delivery, South African distribution is the exception that proves the rule. While living in Uganda, when Angus wanted this Kachere title,The Spirit Dimension in African Christianity, it came to him via ABC in the UK.

In our recently published article, Kenneth tells the fascinating story of the growth of theological research and publishing in Malawi, sprinkled with comparisons to Uganda provided by Angus. He describes the publishing model utilised by Kachere and Mzuni to make available both in Malawi and northwards almost 170 titles on Malawian theology and other subjects, for example, Malawi at Sixty.The breadth of subject and genre is just as impressive as the number of titles: textbooks, Malawian language dictionaries, monographs, and reprints of classic studies (for a list of Mzuni Press titles, see, for Kachere’s, see). All of this is realised using homespun publishing economics; secure what income you can from author-fees, donations and sales to meet external production costs, with scant profit left to meet overheads. The infusion of income from Euro-American sales delivered by ABC is a vital component in this mix. Such publishing practices would stop in their tracks the behemoth academic presses in the North, but as Kenneth observes, the model has the supreme benefit that it works, enabling Malawian theologians and church members to consume what they produce, for example, uMunthu Theology by Augustine Musopole.

Having contributed to getting a similar venture off the ground in Uganda, Angus observes that if such a theological publishing venture had flourished rather than floundering, it could have made greater inroads into making available in the country scholarship from the 150+ doctoral theses on Ugandan Christianity. Of these, while two-thirds are authored by Africans, scholars from the Global North outnumber them two to one when it comes to publication. Again, it is all too easy to slip into lamentation. Instead, our article is a celebration of what can be achieved in African scholarly publishing within a single African country. While Oxford University Press may have published 6,000 tiles in 2023–4 and delivered profits of £99.8 million, it would struggle to place copies of the centenary history into the hands of Church of Central Africa Presbyterian members in Malawi, and co-publish in South Africa and distribute to Euro-America, and allow free downloads globally.

However, we live in the real world where the academic presses in the North still exercise an allure. The burgeoning of Christianity across the Global South has given rise to a new field of study often labelled World Christianity. Yet Kachere and Mzuni Press are outliers when it comes to publishing scholarship on World Christianity. On a prominent listserv for World Christianity scholars, 70% of the publication announcements between 2019 and 2021 were for titles about Christianity in the Global South. Yet 80% were published in the Global North with an average retail price of $70, in comparison to $13 for their Southern-published counterparts. While this is but a single snapshot which can be interrogated on the grounds of language and location, it suggests a trend whereby research does not return to the Southern Christian communities upon which it is dependent. We conclude our article with four suggestions for how Northern-based researchers can return their scholarship to the communities whence it came.

The first is to use a publisher within the region where the research was conducted who also has global distribution capabilities, with ABC’s publishers being the go-to option for African countries. The second is for researchers to encourage Global-North publishers to make co-publishing or rights agreements with a counterpart in the region concerned. Such agreements need to recognise scholarly publishing realities in that region. The third is to consider Open Access (OA) publication, provided funds can be located to meet the high processing charges for OA levied by academic publishers in the North. We are grateful to the publisher of our article, Edinburgh University Press, who made it available OA without charges, as Kenneth is a Malawian-based author. Finally, if all else fails, we recommend researchers secure the highest possible discount from their Global-North publisher for copies to be carried in a suitcase (25-30 copies per 20kg bag) back to the region concerned for a modest launch. Indeed, we conclude the article by asking whether an academic publication, even when returned to the region whence the research came, is the most accessible format to the communities out of which it has been generated. Could the heart of such research be recast into a short booklet in the appropriate language, for sale during a day-long celebration amongst the very people whence it came?

Kenneth and Angus’s article is available Open Access in Studies in World Christianity 31.3 (2025), here.